Prof. Luca Pagani tell about Prof. Svaante Pääbo, Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2022

Pubblicato il: 05.10.2022 17:05

The DNA that constitutes the essential information of any living organism has long been the focus of scientific investigation and industrial applications. While it appears clear why a deeper understanding of “all living things” may be crucial to our scientific, societal and economic wellbeing, the reason why investigating the DNA of “all dead things” is as important may prove harder to fully grasp.

Nevertheless, if nothing in Biology makes sense if not in light of evolution, what else can help us to better understand an evolutionary process than reading it as it happens?

With this in mind, as soon as the very reading of DNA was made possible, a few pioneers set out to extract DNA and ultimately genetic information from mummies, museum specimens, and ancient bones to unveiling their history and placing them within a broader evolutionary narrative.

These early attempts yielded little to no scientific breakthrough. Still they were crucial in highlighting the technological challenges posed by this new endeavour. And as such, these challenges were solved by a technological breakthrough: the introduction of DNA sequencing techniques capable of dealing at high throughput with the small pieces of DNA typical of the ancient, degraded samples (the so called “next generation” sequencing, a pillar of the genomic revolution that started in 2007 and is still ongoing).

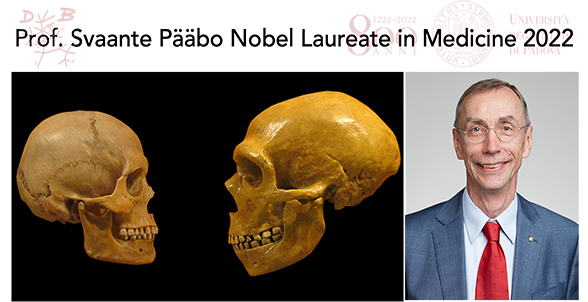

Once overcome the early difficulties, a new field of research was born: paleogenomics. Among the researcher who prepared the ground and were ready for this, Prof. Svante Pääbo and his team at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany stood out for his ambitious plans of expanding our knowledge onto ancient Homo sapiens and to other extinct hominins including the most iconical of them all: Neanderthal.

When the first Neanderthal genome was published in 2010, the full power of paleogenomics was made clear to a broad public. It was no longer just a matter of reconstructing the eye colour of some historical character: anthropologists could now peep into the biology of extinct species and get us closer to understanding what, if anything, really made us human.

An accidental discovery that followed was that our species met and mated with Neanderthals. Such an event encapsulated ~2% of the Neanderthal genome within the DNA of each individual whose ancestors went out of Africa circa 60.000 years ago: that is, around 6 Billion people today.

Beyond refining our knowledge about extinct hominins, the availability of DNA from ancient bones also enabled paleogenomists to identify previously unknown populations, such as the Denisovans, an elusive sister group of Neanderthals who thrived in East and South East Asia and contributed genetic material to the human populations currently living in Near Oceania.

Pääbo’s early efforts, along with the ones of other researchers worldwide such as Eske Willerlsev from Copenhagen and David Reich from Harvard, among others, further developed the field up to a point where the ability to extract and read ancient DNA is now an invaluable tool in the hands of molecular anthropologists and archaeologists who can address long lasting questions in the field, aided by thousands of genomes from the palaeolithic to the modern era.

Such a continuum of human DNA availability through time and space helped researchers to practically visualise the threads of demography and adaptation that shaped contemporary populations.

The success of paleogenomics has already expanded to several animal and plant species and broadened our understanding of domestication processes as well as worrying us about the loss of past biodiversity. On the one hand, the reception of the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 2022 by Svante Pääbo witnesses the importance of past individuals to better understand the present of our species. On the other, the future of ancient DNA is ever bright, with molecules being read out of more and more organisms or even just out of soil sediments, the dynamics of ancient epidemics being understood and, hopefully soon, the genome of Homo erectus and even more ancient hominids eventually evoked to tell us their yet unwritten tale.

Luca Pagani