Researchers sequence first genome from ancient Egypt

Pubblicato il: 11.07.2025 13:39

We report here the text from the press release kindly provided by the Francis Crick Institute (London, UK). The original press release can be found here:

Researchers sequence first genome from ancient Egypt | Crick

Segue la traduzione in italiano.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Researchers from the Francis Crick Institute and Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) have extracted and sequenced the oldest Egyptian DNA to date from an individual who lived around 4,500 to 4,800 years ago, the age of the first pyramids, in research published today in Nature.

Forty years after Nobel Prize winner Svante Pääbo’s pioneering attempts to extract ancient DNA from individuals from ancient Egypt, improvements in technology have now paved the way for the breakthrough today, which is also the first whole genome (the entire set of DNA in an individual) from ancient Egypt.2

During this period of ancient Egyptian history, archaeological evidence has suggested trade and cultural connections existed with the Fertile Crescent – an area of West Asia encompassing modern-day Iraq, Iran and Jordan, among other countries.

Researchers believed that objects and imagery, like writing systems or pottery, were exchanged, but genetic evidence has been limited due to warm temperatures preventing DNA preservation.

In this study, the research team extracted DNA from the tooth of an individual buried in Nuwayrat, a village 265km south of Cairo, using this to sequence his genome.

The burial had been donated by the Egyptian Antiquities Service, while under British rule, to the excavation committee set up by John Garstang. It was initially housed at the Liverpool Institute of Archaeology (which later became part of the University of Liverpool) and then transferred to World Museum Liverpool.2

The individual died at some point in the overlap between two periods in Egyptian history, the Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom periods, and had been buried in a ceramic pot in a tomb cut into the hillside. His burial took place before artificial mummification was standard practice, which may have helped to preserve his DNA.

By analysing his genetic code, the researchers showed that most of his ancestry mapped to ancient individuals who lived in North Africa. The remaining 20% of his ancestry could be traced to ancient individuals who lived in the Fertile Crescent, particularly an area called Mesopotamia (roughly modern-day Iraq).

This finding is genetic evidence that people moved into Egypt and mixed with local populations at this time, which was previously only visible in archaeological artefacts. However, the researchers caution that many more individual genome sequences would be needed to fully understand variation in ancestry in Egypt at the time.

By investigating chemical signals in his teeth relating to diet and environment, the researchers showed that the individual had likely grown up in Egypt.

They then used evidence from his skeleton to estimate sex, age, height, and information on ancestry and lifestyle. These signs suggested he could have worked as a potter or in a trade requiring comparable movements, as his bones had muscle markings from sitting for long periods with outstretched limbs.

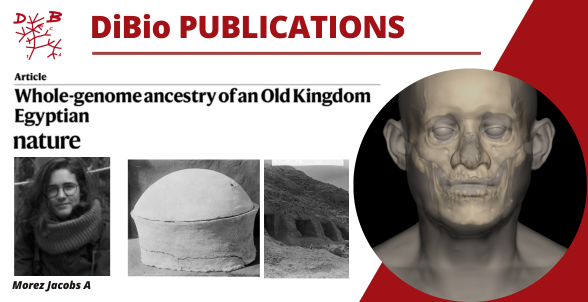

Adeline Morez Jacobs, Visiting Research Fellow and former PhD student at Liverpool John Moores University, former postdoctoral researcher at the Crick, now postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Biology (UniPD) and first author, said: “Piecing together all the clues from this individual’s DNA, bones and teeth have allowed us to build a comprehensive picture. We hope that future DNA samples from ancient Egypt can expand on when precisely this movement from West Asia started.”

Linus Girdland Flink, Lecturer in Ancient Biomolecules at the University of Aberdeen, Visiting Researcher at LJMU and co-senior author, said: “This individual has been on an extraordinary journey. He lived and died during a critical period of change in ancient Egypt, and his skeleton was excavated in 1902 and donated to World Museum Liverpool, where it then survived bombings during the Blitz that destroyed most of the human remains in their collection. We’ve now been able to tell part of the individual’s story, finding that some of his ancestry came from the Fertile Crescent, highlighting mixture between groups at this time.”

Pontus Skoglund, Group Leader of the Ancient Genomics Laboratory at the Crick and co-senior author, said: “Forty years have passed since the early pioneering attempts to retrieve DNA from mummies without successful sequencing of an ancient Egyptian genome. Ancient Egypt is a place of extraordinary written history and archaeology, but challenging DNA preservation has meant that no genomic record of ancestry in early Egypt has been available for comparison. Building on this past research, new and powerful genetic techniques have allowed us to cross these technical boundaries and rule out contaminating DNA, providing the first genetic evidence for potential movements of people in Egypt at this time.”

Joel Irish, Professor of Anthropology and Archaeology at Liverpool John Moores University and second author, said: “The markings on the skeleton are clues to the individual’s life and lifestyle – his seat bones are expanded in size, his arms showed evidence of extensive movement back and forth, and there’s substantial arthritis in just the right foot. Though circumstantial these clues point towards pottery, including use of a pottery wheel, which arrived in Egypt around the same time. That said, his higher-class burial is not expected for a potter, who would not normally receive such treatment. Perhaps he was exceptionally skilled or successful to advance his social status.”

In future work, the research team hopes to build a bigger picture of migration and ancestry in collaboration with Egyptian researchers.

Read the full article online here:

Whole-genome ancestry of an Old Kingdom Egyptian | Nature

Notes

The technique used was called ‘whole genome sequencing’ where the entire DNA sequence is sequenced. This is different to previous methods which involved looking for specific markers in the DNA.

The export of the burial outside of Egypt by archaeologist John Garstang was approved under the 'partage' system, a legal framework established in 1883, which, until 1983, allowed the division of archaeological finds between Egypt and foreign institutions. Under this system, materials deemed sufficiently represented in Egyptian collections could be approved for export by museum authorities in Cairo. John Garstang exported eight burials to the UK under this framework out of more than 900 excavated during his career. The remaining burials were kept in Egypt, including those of the nearby Beni Hasan necropolis, currently held at the Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Traduzione in italiano

Riportiamo qui il testo del comunicato stampa gentilmente fornito dal Francis Crick Institute (Londra, Regno Unito). Il comunicato originale è disponibile qui:

Researchers sequence first genome from ancient Egypt | Crick

Ricercatori del Francis Crick Institute e della Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) hanno estratto e sequenziato il DNA più antico mai recuperato dall’Egitto, appartenente a un individuo vissuto circa 4.500-4.800 anni fa, all’epoca delle prime piramidi, secondo quanto riportato oggi in una pubblicazione su Nature.

Quarant’anni dopo i tentativi pionieristici del Premio Nobel Svante Pääbo di estrarre DNA antico da individui dell’antico Egitto, i progressi tecnologici hanno ora reso possibile questo importante traguardo: si tratta anche del primo genoma completo (cioè l’intero insieme del DNA di un individuo) mai ottenuto dall’antico Egitto.²

Durante questo periodo della storia egizia, le evidenze archeologiche suggerivano l’esistenza di scambi culturali e commerciali con la Mezzaluna Fertile – un’area dell’Asia occidentale che comprende l’attuale Iraq, Iran e Giordania, tra altri paesi.

I ricercatori ritenevano che oggetti e simboli, come i sistemi di scrittura o la ceramica, fossero stati scambiati, ma le prove genetiche erano finora limitate a causa delle alte temperature che ostacolano la conservazione del DNA.

In questo studio, il team ha estratto il DNA da un dente di un individuo sepolto a Nuwayrat, un villaggio situato a 265 km a sud del Cairo, utilizzandolo per sequenziare il suo genoma.

La sepoltura era stata donata dal Servizio delle Antichità Egizie, durante il periodo di dominio britannico, al comitato di scavo istituito da John Garstang. Inizialmente conservata presso il Liverpool Institute of Archaeology (successivamente parte dell’Università di Liverpool), fu poi trasferita al World Museum di Liverpool.²

L’individuo morì in un periodo compreso tra la fine del Periodo Dinastico Arcaico e l’inizio dell’Antico Regno, e fu sepolto in un vaso di ceramica in una tomba scavata nel fianco di una collina. La sepoltura risale a un’epoca precedente alla pratica diffusa della mummificazione artificiale, il che potrebbe aver favorito la conservazione del DNA.

Analizzando il suo codice genetico, i ricercatori hanno dimostrato che la maggior parte della sua ascendenza genetica corrispondeva a individui antichi del Nord Africa. Il restante 20% circa risultava invece legato a individui antichi provenienti dalla Mezzaluna Fertile, in particolare da un’area chiamata Mesopotamia (corrispondente grossomodo all’attuale Iraq).

Questa scoperta costituisce una prova genetica del fatto che popolazioni si siano spostate verso l’Egitto e si siano mescolate con le popolazioni locali in quel periodo, una dinamica che finora era visibile solo attraverso i reperti archeologici. Tuttavia, i ricercatori sottolineano che sarà necessario sequenziare molti altri genomi individuali per comprendere appieno la variazione genetica presente nell’Egitto di quell’epoca.

Analizzando i segnali chimici presenti nei denti relativi a dieta e ambiente, i ricercatori hanno mostrato che l’individuo molto probabilmente era cresciuto in Egitto.

Hanno poi esaminato lo scheletro per stimare sesso, età, altezza e per ottenere informazioni su ascendenza e stile di vita. I segni ossei suggerivano che l’individuo potesse aver lavorato come vasaio o in un mestiere con movimenti simili, poiché le ossa mostravano segni muscolari compatibili con lunghi periodi trascorsi seduto con gli arti distesi.

Adeline Morez Jacobs, Visiting Research Fellow ed ex dottoranda presso la Liverpool John Moores University, ex post-doc al Crick ed attualmente assegnista di ricerca presso il Dipartimento di Biologia (UniPD) e prima autrice dello studio, ha dichiarato:

«Unendo tutti gli indizi ricavati dal DNA, dalle ossa e dai denti di questo individuo, siamo riusciti a ricostruire un quadro completo. Speriamo che futuri campioni di DNA dall’antico Egitto possano chiarire meglio quando, precisamente, iniziarono questi movimenti di popolazioni dall’Asia occidentale.»

Linus Girdland Flink, docente di Biomolecole Antiche presso l’Università di Aberdeen, Visiting Researcher alla LJMU e co-autore senior, ha affermato:

«Questo individuo ha attraversato un percorso straordinario. Visse e morì durante un periodo cruciale di cambiamento nell’antico Egitto, il suo scheletro fu scoperto nel 1902 e donato al World Museum di Liverpool, dove sopravvisse ai bombardamenti del Blitz che distrussero gran parte della collezione di resti umani. Oggi siamo riusciti a raccontare parte della sua storia, scoprendo che una parte della sua ascendenza proveniva dalla Mezzaluna Fertile, evidenziando mescolanze tra gruppi in quel periodo.»

Pontus Skoglund, responsabile del Laboratorio di Genomica Antica del Crick e co-autore senior, ha dichiarato:

«Sono passati quarant’anni dai primi tentativi pionieristici di estrazione del DNA da mummie, senza però riuscire a sequenziare un genoma egiziano antico. L’antico Egitto è un luogo ricco di storia scritta e reperti archeologici, ma la difficile conservazione del DNA ha impedito finora di ottenere un quadro genetico dell’ascendenza in epoca antica. Grazie alle nuove e potenti tecniche genetiche, siamo riusciti a superare questi ostacoli tecnici ed escludere contaminazioni, ottenendo così la prima prova genetica di potenziali movimenti di popolazioni in Egitto in quell’epoca.»

Joel Irish, professore di Antropologia e Archeologia alla Liverpool John Moores University e secondo autore, ha aggiunto:

«I segni presenti sullo scheletro offrono indizi sulla vita e sulle abitudini dell’individuo – le ossa del bacino risultano ingrandite, le braccia mostrano segni di movimenti ripetitivi avanti e indietro, e vi è una marcata artrite solo nel piede destro. Anche se indizi indiretti, questi elementi fanno pensare a un’attività di ceramista, magari con l’uso di una ruota da vasaio, che comparve in Egitto proprio in quel periodo. Tuttavia, la sepoltura di classe elevata non è quella attesa per un vasaio, che normalmente non avrebbe ricevuto un trattamento simile. Forse era un artigiano eccezionalmente abile o di successo, al punto da elevarsi di status sociale.»

In futuro, il team di ricerca spera di ampliare il quadro su migrazioni e ascendenza collaborando con ricercatori egiziani.

Leggi l’articolo completo online qui:

Whole-genome ancestry of an Old Kingdom Egyptian | Nature

Note:

¹ La tecnica utilizzata si chiama whole genome sequencing (sequenziamento dell’intero genoma), in cui viene letta tutta la sequenza del DNA. È diversa dai metodi precedenti che cercavano solo marcatori specifici nel DNA.

² L’esportazione della sepoltura fuori dall’Egitto da parte dell’archeologo John Garstang fu approvata nel contesto del sistema di “partage”, un quadro legale istituito nel 1883 che, fino al 1983, consentiva la divisione dei reperti archeologici tra l’Egitto e le istituzioni straniere. In base a questo sistema, i materiali considerati sufficientemente rappresentati nelle collezioni egiziane potevano essere autorizzati all’esportazione dalle autorità museali del Cairo. John Garstang esportò nel Regno Unito otto sepolture nell’ambito di questo sistema, su oltre 900 scavate nel corso della sua carriera. Le sepolture rimanenti rimasero in Egitto, comprese quelle della vicina necropoli di Beni Hasan, oggi conservate presso il Museo Egizio del Cairo.